Written by John Sander

Viscosity Classifications

Fortunately for the end-user, various technical societies have created classifications that are used by lubricant manufacturers when formulating the proper viscosity grade of lubricant needed for their equipment. These viscosity classification systems are commonly used to describe both industrial and automotive lubricants. These standardized viscosity ranges are used by lubricant formulators, original equipment manufacturers and lubricant consumers when labeling, marketing, specifying and using lubricants.

Fluid Lubricant Viscosity Classifications

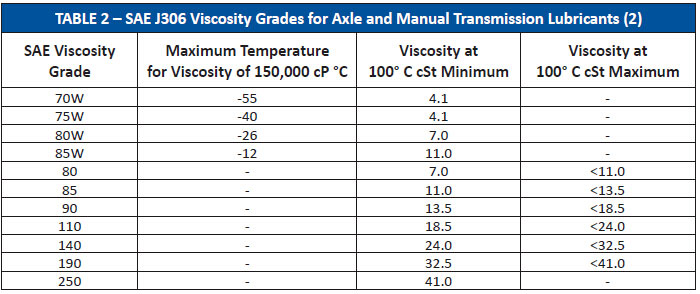

The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) has created two viscosity standards for automotive lubricants. SAE J300 is a viscosity classification for engine oils, and SAE J306 is for axle and manual transmission lubricants. The J300 viscosity grades and their requirements are summarized in Table 1, while those for J306 are shown in Table 2. In both of these classifications, the grades denoted with the letter "W" are intended for use in applications operating in low-temperature conditions. The "W" was originally coined for lubricants that were considered "winter grade." Today, these products are formally called multigrade lubricants, whereas the grades without a "W" are recognized as monograde, or straight grade, lubricants.

* For 0W40, 5W40 and 10W40 Grades

** For 15W40, 20W40, 25W40 and 40 Grades

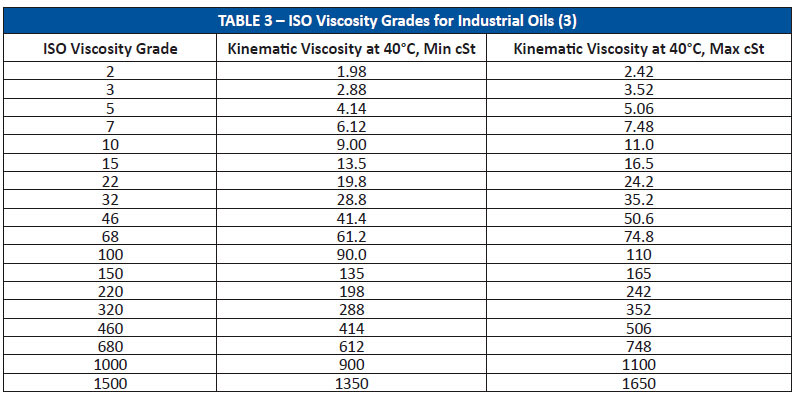

Industrial fluids are also specified according to various viscosity classifications. The most frequently used industrial viscosity classification was jointly developed by ASTM International and the Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers (STLE). It was recognized as ASTM D2422. This method originally standardized 18 different viscosity grades measured at 100°F in Saybolt Universal Seconds (SUS). It was later converted to more universally accepted metric system values measured at 40°C. The system eventually received international acceptance. These viscosity ranges are denoted in Table 3 and are usually recognized as "ISO viscosity grade numbers", often shortened to "ISO VG numbers".

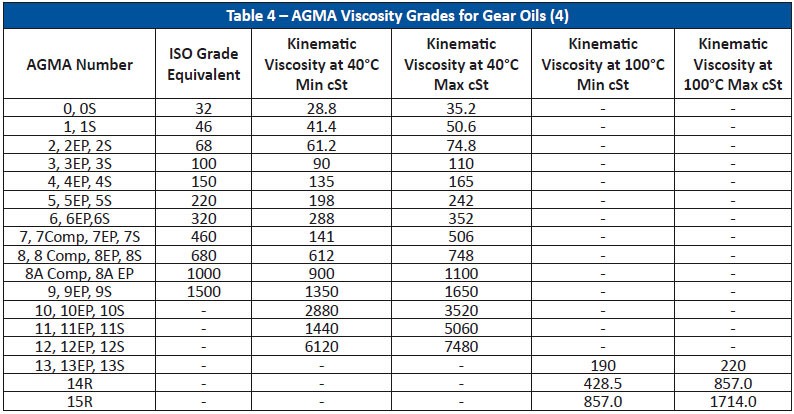

The American Gear Manufacturers Association (AGMA) has also created a commonly used viscosity classification system, which is partially based off the ISO VG system, noted in Table 4. The AGMA numbers let the user know the ISO viscosity grade and some basic information about the gear lubricant's chemistry. If the product is a mineral oil that contains only rust and oxidation (R&O) additives, it will be recognized with only the AGMA number. If it is a mineral oil with extreme pressure additives, it is recognized with the AGMA number followed by the "EP" designation. AGMA numbers followed by an "S" denote synthetic gear oils. Compounded gear oils contain 3% to 10% fatty or synthetic fatty oils and are noted by the AGMA number with "Comp" after it. Some gear oils contain residual compounds called diluent solvents that are used to temporarily reduce the viscosity making it easier to apply. In this case, the AGMA number is followed by an "R", which describes product prior to addition of diluents solvent.

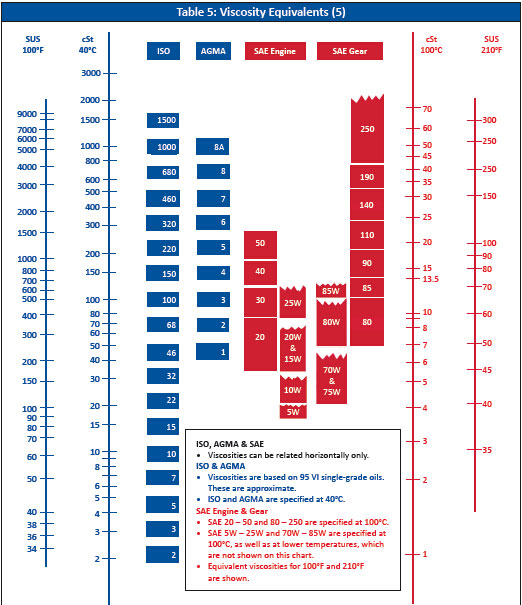

Now do all of these viscosity grades seem easier to understand? Okay, maybe not yet, so Table 5, a viscosity equivalent chart, provides a comparative illustration of all of the grades shown in tables 1 through 4. For example, the chart indicates that an SAE 50 engine oil and an SAE 90 gear oil are the same viscosity. This might surprise you if you are thinking that gear oil is always thicker than engine oil. However, as shown in the table, they are nearly equivalent.

As with anything, viscosity classifications have changed over time. As mentioned above, viscosity used to be commonly recorded in SUS units in the United States. As the economy has become more global, different standards organizations have worked together to standardize units of measure, including viscosity units. Some older equipment is still in operation that specifies the lubricant viscosity in the older units. The OEM might designate it with SUS units, while end users might refer to it in "seconds", e.g. "I need a 100-second oil for this machine". Fortunately, there are common conversions that can be used to estimate the cSt value from the SUS value.

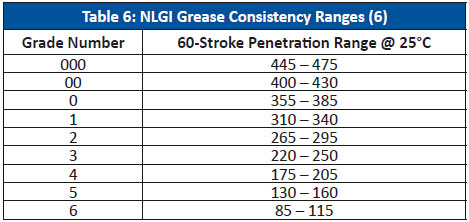

Grease Consistency Classifications

In some lubricant applications, it is impossible to contain a fluid lubricant. For these applications, greases are used. A simple description of grease is a semi-solid lubricant composed of base fluid, additives and a thickener. The thickener in grease is added in most cases to help keep the lubricant in place on applications where a fluid lubricant would run off and only provide lubrication for a very short time. Because greases are not a fluid, their resistance to flow is generally called consistency instead of viscosity. The NLGI created a set of ranges that have become the standard by which most greases are produced, marketed and sold. These ranges are based upon the ASTM D217 cone penetration test after 60 strokes of shear, described in more detail later. The NLGI ranges are listed in Table 6. The #000 greases have a runny consistency similar to cooking oil, while the consistency of #6 greases is similar to a block of cheese.