By John S. Evans, B.Sc.

Causes of friction

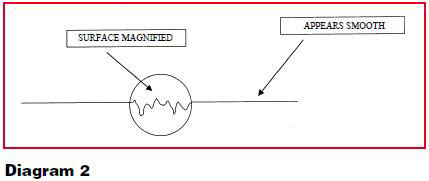

Surfaces that appear smooth and shiny to the naked eye will show peaks and furrows when examined with a microscope or even a magnifying glass. This does not mean that the component has been poorly machined but that components manufactured to prescribed tolerances may still have fairly rough surfaces at microscopic level (see Diagram 2).

When two surfaces are brought into contact, it is the tips of the peaks that actually touch, meaning that large areas of the surfaces never come into contact. For example, the contact area of two flat steel surfaces subjected to a pressure of 0.5 kgcm(-2) is about 1/40 000th of the apparent surface area. The size of the contact area not only depends on the surface area and roughness but also on the load acting on the two surfaces. The peaks where contact actually takes place are called asperities.

Because it is the asperities that touch and because they make up a very small surface area, very high pressures and temperatures are achieved which can cause metal deformation and cold welding to take place. When the surfaces slide over each other, microscopic welds are produced between peaks which, due to the relative motion, are then torn apart.

The laws of friction apply to one clean metal surface sliding over another. The laws break down when thin metal films or oxidised surfaces are considered. They also do not apply to very hard surfaces (eg. a diamond) or very elastic surfaces (eg. rubber) where the contact area no longer depends on pressure.